from play to precious: what do we value?

and is it all worth it anyway?

Reposted from the Light the Lamp Newsletter.

Let the children play

Earlier this month, one of my jewelry clients (who also works in education) shared this article by Dr. Peter Gray titled “Why Kids Are Suffering Today” on her LinkedIn profile. Given how pivotal teaching GenZ has been for me (case in point: starting this collective), I clicked on the link. Here is an excerpt from the introduction:

I have long been concerned with the continuous rise, over roughly the past 50 years, in the rates of depression, anxiety, and suicides among children and teens. This increase in suffering has occurred during a period in which young people have been subjected to ever-increasing amounts of time being supervised, directed, and protected by adults—in school, in adult-run activities outside of school, and at home—and have experienced ever less opportunity to play freely and in other ways pursue their own interests and solve their own problems… The pressure and continuous monitoring and judgments from adults, coupled with the loss of freedom to follow their own interests and solve their own problems, results in anxiety, depression, and general dissatisfaction with life.

Now… I examine this relationship between changes in how young people are treated and the decline in their mental well-being through the lens of BPNT [Basic Psychological Needs Theory]. My contention is that we have, over decades, been decreasing children’s opportunities to experience autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

I think it’s fair to say that for someone deeply concerned with the fate of humanity and the planet, the well-being of children is paramount if we are to nurture any hope for improvement over the current state of affairs. So naturally, the last statement above stopped me in my tracks. Dr. Gray goes into detail about the ways in which this manifests in each of the areas, including (but not limited to) things like:

decreasing children’s opportunities to pursue their own paths due to increased demands of homework and adult-directed extra-curricular activities

overvaluing (or exclusively valuing) academic achievement as opposed to other areas children might excel and flourish (this becomes a double whammy when academic achievement is something forced on the child and has therefore deprived them of autonomy)

depriving children of time and opportunity to simply play with peers, which allows them to develop relationships not affected by adult influence/priorities/values; bonding like this during play would have a major role in decreasing feelings of alienation and loneliness

I could give you dozens of examples of how I’ve witnessed all of these with the college-aged students I have been interacting with over the last few years. Of course there are a few exceptions, but the thing I’ve been most surprised by is the bewilderment, apprehension and even resistance that I’ve encountered from my students when it comes to the subject of exploration and “play.” I teach fashion design, textiles and portfolio development — all subjects where a healthy dose of experimentation and failure leads to greater development in the end. Now, to me as the educator, “playing” (aka “trying shit out to see what happens”) is one of the joys of being in design school, because the way I see it, design school is the lowest stakes environment you could hope for! You won’t be able to engage in these experiments in the vast majority of jobs later on in life, and even if you wanted to try things out for your personal projects, you’d be hard-pressed to find the time and energy to do so once you’re in the daily grind of the workforce such as it is… So I say, PLAY! FAIL! And do it NOW because I’m giving you full permission to go nuts.

But usually when I’ve made announcements like these, I’m met with blank stares from my students. For some, the concept of play is completely alien: “What do you mean you just want me to try things? What does it need to look like?” (My answer: it doesn’t need to look like anything — don’t edit, don’t erase things, just explore and see what you discover.) For others, there is a lack of trust, and they think in spite of what I’ve just told them, I’ll penalize them for “failing” to achieve something grand as a result of their experiments. Most are just concerned that if everything they do isn’t genius their grades will suffer: “How do I get an A in your class?” (Note: as a student who was herself largely dependent on scholarships to support my education, I understand preoccupation with maintaining a beefy GPA. But these special circumstances aside, as almost everyone in fashion can attest, no one in the fashion industry will ever ask you for your GPA.)

As much as I emphasize that the process is just as important (if not more so, in this case) than the end result, and regardless how many schizophrenic croquis books I show them filled with my own failed experiments from when I was a student, the fear and anxiety remain. Most students are always editing and curating themselves, because this is the strategy of survival for the world we have grown accustomed to. And then we wonder why students don’t feel safe to express themselves fully and show up as their authentic selves. How can they when it seems like all the world *really* wants to see is their perfect highlight reel so they can fit in and be deemed “successful”?

“Are you doing this for validation or is there another purpose?”

As an independent designer, I think it’s crucial be in community with others who are on a similar journey. One of my closest creative confidantes, a brilliant independent designer in her own right, was listening to me the other day as I went down a comparison rabbit hole. After I was done whining (hey, it happens to the best of us), she said, “My question for you is why are you doing creative work to begin with? Is it for validation? Or is there another purpose? These are important questions.”

I agree: these are important questions.

Designers can start brands for a multitude of reasons, and there is no right or wrong answer here as long as you are honest with yourself. Honesty allows you to stay true to your work, whatever that truth is. And in my case, she was right that I had to put the focus back on myself because the reason I began creating the things I’m creating now came from a very personal and even auto-biographical place.

However (you knew there was a “however” coming, didn’t you?):

Demonizing the need for external validation is just as narrow-sighted as proclaiming the highly personal as the pinnacle of design value.

I’ll illustrate this point with another anecdote.

A couple weeks ago, the jewelry school where I’ve been attending classes celebrated its 10-year anniversary with a large exhibit of contemporary art jewelry from the students who had taken classes there over the years. It was an extremely moving affair, showcasing a variety of interpretations on the common theme of “roots.” Throughout the five days the exhibition ran, there was an opening with the opportunity to meet and speak to each of the artists, live performances, and time and space to gather with classmates old and new in joy and celebration.

In class the week after the exhibition closed, one of my classmates, a working mother of a young boy, expressed how wonderful it was that this event had taken place. Her reasoning? One of her son’s classes had canceled a year-end celebration and exhibition of student work, which had now left all the kids feeling like everything they were doing was pointless. Part of it is the whole “if a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, did it make a sound” philosophy. But part of it also goes back to what I was talking about in the previous section, the need for children to belong and be acknowledged for their unique gifts rather than what is expected of them. External validation (in this case: showing work to the public and being celebrated for it) is also important. Adults need that too, regardless of why they set out to make that work in the first place. And so, in the funny way not uncharacteristic of how life works, we’ve come full circle in this discussion.

Is it all worth it?

Neckpiece in 24, 22, 20, 18, 16, 14 and 12K gold and 999 silver repoussé metalwork by Dimitris Nikolaidis

Detail of Considered Objects waistcoat handmade from antique kimono fabrics by Sara Sakanaka

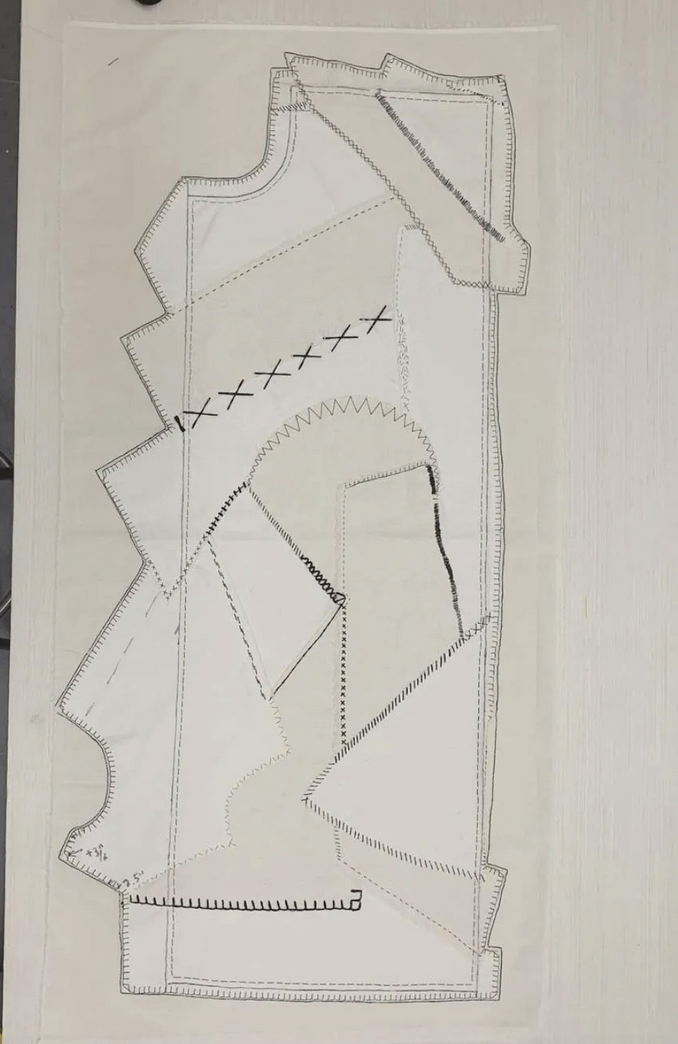

Panel of trench made from scraps of cotton twill and hand embroidered by Harrison Bradt

Finally this month, some thoughts on value.

The more I think about it, the more I see this entire newsletter becoming a conversation about what we value, because I believe our skewed values as a society are what have brought us to the precarious state of the world in the year 2022. And because art and design (and specifically fashion) is the industry where I have some level of expertise, this is the lens through which I examine those values. But I digress…

The first image in this section, the neckpiece by Dimitris Nikolaidis, took 600 hours of work to complete. It is made entirely by hand directly in the metals listed in the description. The second image shows a detail on inside of a waistcoat by Considered Objects designer Sara Sakanaka with her signature pressed flower appliqué: these are scraps of silk chiffon carefully shaped and painstakingly hand embroidered onto a waistcoat made from antique kimono fabrics. While the waistcoat can be worn inside out, this detail is really there as an offering for the wearer, another stanza in the poetry that is Sakanaka’s garments. The last photo is a panel of a trench coat by Harrison Bradt, from a collection that he meticulously spent over two years working on, the crux of which is extensive embroidery and handwork techniques. It is a collection he poured his heart and soul into because, as he said, “I don’t know what else I would do,” while simultaneously doing full-time work for others.

Why am I showing you these things?

For one thing, I’m showing you these things because they’re beautiful, and most likely things you’ve never seen or alternately things that would easily get overlooked because they’re not on some influencer’s Instagram feed. But I’m also showing you these things because of the sheer amount of time and labor (and not to mention love) that went into them - time and labor that, if we were to assign a respectable hourly wage to, would render them nothing short of priceless. This brings to the forefront the whole notion of “perceived value,” a driving force in the world of retail and something that every designer finds themselves doing battle with more often than not in their professional life.

This notion of “perceived value” refers to monetary value, given that money is the embodiment of access, agency, freedom, and power for most things nowadays. I plan to talk about the double-edged sword of pricing items what they’re worth in a future newsletter, but today I wanted to leave you with the question that one of the creators above posed the other day:

“You know, lately I’ve started to ask myself if it’s really worth it - the time I put into it? Because the world is what it is today. I mean, I think every artist has to ask themselves that question.”

It was heartbreaking to hear them admit this, but also it’s not like they weren’t voicing the doubts many of us have on a daily basis. They know they could never sell that piece for the price it’s actually worth. Just like so many other artists and designers, including myself, we do other things to make a living so we can keep doing what keeps us alive. But I am choosing to believe this doesn’t have to be the case forever. I am choosing to believe that if we all talk about what we actually do and why we do it, why it’s important to us to spend those hours doing something by hand in lieu of a faster, and likely more “perfect,” machine alternative, how every fabric or stitch or element was a choice, carefully considered, that we, the creators made according to our vision… if we talk about all of these things and share these stories, these details, the world will remember what it’s like to value the work of people doing things out of love for their craft again, and we become a better society for it.